Published in the Social Education Association of Australia Journal, Canberra (8/2000) under the theme - Social Education in the New Millennium: The Challenge to Change

Introduction

In 1863 'Tokugawa' Japan was subjected to the gun boat diplomacy of U.S. Navy Commodore Matthew Perry and his fleet of 'black ships'. This action was a pre-cursor to the modernising 'Meiji' era that brought about rapid change in Japan. In the last two years Japan has suffered from the modern fiscal equivalent of Cmdr. Perry as the U.S. and Europe demand wide ranging financial reform and an opening up of the Japanese economy. As has happened in S-E Asia, Japan is now having economic rationalism forced upon it. In some ways its perceived (and heavily praised) strengths of the 1980's have now become its liabilities. The nation faces a crisis of confidence as lifetime employment is no longer assured and unemployment reaches a post war high of 4.8% (ABC News 29.7.99)

This paper is based on experiences gleaned from the author's two year tenure (1995-1997) as a teacher in the community of Omi-machi (Blue Sea Town, hereafter referred to as Omi), Japan. Unfortunately there is a dearth of recent scholarly Japanese opinion on its education system. However some books, such as those by Kaigo (1965), Amano and Aso (1972), Kobayashi (1975), and Fujita (1978) show that there has been much continuity of educational methods in Omi over the last thirty years, aside from the growing use of technology. This is born out in the case study of Nichu chugakko (Junior High School) by John Singleton (1967).

The west has always found this land its people somewhat of an enigma. Japan is an ancient country with deeply rooted folkways and mores. Change is something that does not come easily or quickly, especially in a conservative rural area such as Omi.

The notion of "community" is probably one of, if not the most, deeply imbedded mores of Japanese society. It has successfully brought low unemployment, divorce and crime rates, plus large spending on education. Unfortunately this is due to change over the next ten to twenty years as a huge transformation (due to economic imperatives and other socio-economic factors) is forced upon society. This became a major concern to the author during his tenure.

This school, like so many others, must "...begin to operate in a mode consistent with the future rather than with the past." (Beare & Slaughter 1993) Therefore, in this paper options will be canvassed that perhaps will ease the pain of this change - using Omi as a micro example. It is hoped not to impose ethno-centric assumptions of superior thought, but will attempt to put forward a model that, working within the theory of nihonjinron ('Japaneseness'), can be embraced and 'owned' by the community. To understand education in any context we must study it as it is - deeply rooted "..in the culture of which it is an integral part and which it serves." (Singleton 1967)

The Japanese idea of how a community best functions can briefly be expressed thus,

"...their behaviour is influenced by an awareness of the order and rank of each person. Conformity is the norm [and]...is influenced by the behaviour of others,...what others will think of him/her. [It] can be partly explained by their homogeneity and a tradition of unnecessary friction. The Japanese put much importance on harmony..." (Honen 1988)

But while group harmony may be pre-eminent, it does not ensure 'community' as such. Neither does it mean that problems will be recognised and/or satisfactorily remedied. This will be further discussed later in this paper.

Also to be considered is the clash of 'old' Japanese ideas of community with the 'new' Western culture of individualism, as put by Furnivall,

"...between the eastern system resting on religion, personal authority, and customary obligation, and the western system resting on reason, impersonal law, and individual rights" (Nisbet 1962)

One example of this is where many Japanese students today forsake natural consensus to pursue individuality. This stands in stark contrast to the prevailing mood of the community and teachers. It can cause discipline problems, which are hard to rectify because the Japanese school system is not attuned to dealing with such problems. Conversely it can also cause 'bullying' where a student is overtly harassed by others for being different.

Parental and school roles are seen as less intertwined, and parents are not inclined (or encouraged) to truly participate in the running of schools. This is a growing problem at Omi chugakko which along with the surrounding community will be focus of my case study. It must be noted that when considering any solutions one cannot automatically apply 'western' ideas.

This is partly because communities in Japan suffer from the same moral dilemma Nisbet (1962) claims about China and India,

"The displacement of function must lead in the long run to the diminution of moral significance in the old; and this means the loss of accustomed centres of allegiance, belief, and incentive."

In Japanese junior high schools the role of an educator is seen as one of,

"...cultivating the qualities that young people will need to play useful roles in the nation and society, [plus teaching]...fundamental knowledge and skills necessary for socially useful occupations." (Honen 1988)

Therefore at this time of their life the Japanese student is not being intellectually or academically challenged, rather they are being trained to take his or her 'place' in the larger community. This puts a stress on "...social progress rather than...intellectualism". (Bambach 1977)

The result usually produced is a more 'level field' of academic achievement as lamented by Maroya (1985). But it also often brings a harmony where older children tend to be more supportive and patient with the younger ones. When a student rejects these ideas and begins to assert their individual rights, group harmony fails, as can discipline too. In a positive light, some students assert their individualism by choosing to 'rise above the pack' academically.

The Japanese, particularly in rural communities, have only begun in recent years to deal with many social issues, viz, dislocation, a breakdown of traditional roles, family and community, youth alienation, growing unemployment, and an emerging conflict between western and eastern thought. The challenge for a school is helping to instigate meaningful change, whilst respecting what is commonly known as 'the Japanese way'.

At the same time the notion of 'community' must be challenged. Whilst there may be a constant striving for 'community', is not the definition of community changeable and evolving? Communities over the ages have had much fewer choices than we have today. We have gone from small gatherings of people with little knowledge of more than their immediate surroundings, to today's global village.

My contention is that we still have 'community' - only wider, constantly changing, fractured, and more impersonalised. We cannot regain the village community of yesteryear. Modern technology is granting us new ideas of identity. We need to face the problems of community looking forward, not back.

Any process must also ensure that 'culture' is not misused in the interests of power and/or influence (Beare, et al, 1989). Tomoyuki Iwashita (1982) contends that, "...Japan's education and socialisation processes do not equip people with the intellectual and spiritual resources to question and challenge the status quo.". People in Japan do not want to change - but change is being foisted upon them. We must harness these larger forces and attempt to apply them on a smaller scale to the local school/ community.

Profile of the school community

Omi is a rural machi (town) located on the Japan Sea coast in Niigata Prefecture, about four hundred kilometres north-west of Tokyo (see below). The town also includes two small mura (villages), Oyashirazu and Ichiburi, located six kilometres and thirteen kilometres respectively further down the coast from Omi.

The town is a classic case of rural decline. In the last 30 years the population has decreased from around 17,000 to today's level of 10,590. After graduating from high school most young people are forced to move to major population centres for university or in search of work. This is reflected in the population, with the majority of residents aged over 35. Concurrently the number of students attending Omi chugakko has fallen from 568 to 344 in the last 10 or so years. The fall has been more pronounced in latter years (495 in 1990).

Local unemployment figures are unavailable, so therefore can not be compared to the national average (refer Introduction). The population is predominantly middle-class, and the average annual wage in 1990 (the most recently available figure) was ¥4,528,260 (US$40,000). Many of the 'blue collar' jobs at local factories have been taken up by outside residents (mostly single males), who reside in company supplied dormitories. The main employer in Omi is Denka Ltd., with two large factories producing cement and chemicals.

The other main employer is the town and governmental agencies with one civil servant for every 76 people. Omi has many well funded facilities, especially for a town of its size. These include regular local bus and train services (but only a few long distance services), an indoor heated pool, gymnasium, baseball field, several small local parks, mountain camping sites, plus a new natural history museum, library, and performance hall seating 500 people.

Contrary to this there are only a few small local shops, supermarkets and restaurants, and no entertainment facilities (movie theatre, bowling alley, amusement arcade, etc.) - especially those that would appeal to younger people. With the declining population many such facilities (such as the movie theatre and baseball stadium) have been closed and demolished in recent years.

The classic 'nuclear' family is the norm, with few single parent families. As a rule of thumb, there would be only one or two children in each classroom who come from a single parent household. There are few organised interest groups (in a western sense), as people rely on traditional networks and family ties. There is virtually no ethnic diversity in the town - as is generally the case outside Japan's main population centres.

Profile of the School

Students come to Omi chugakko from the four local shogakko (elementary schools) - Omi, Tazawa, Utatonami, and Ichiburi. All schools and kindergartens are run by the local Board of Education, and this is ultimately where all decisions are made. Omi chugakko caters for Years Seven, Eight, and Nine. At the end of Year Nine 50% of students graduate to the kokko (senior high school) and 40% to the shokko (commercial and industrial college) in neighbouring Itoigawa City. The remaining 10% drop out to find employment, or move further afield to more specialised schools.

When this study first commenced in the 1995/96 school year the school had 344 enrolled students. There were three Year Seven classes (36-38 students in each), three Year Eight classes (35-37 in each), and four Year Nine classes (30 in each). By the 1998/9 school year enrolment had dropped slightly with a total of three classes in each grade. As with most schools, the students are of mixed ability - a number of outstanding students, a similar proportion of underachievers, and the rest falling somewhere in between.

There are no special support programs for students and all students are required to be a member of a school club which meets out of school hours (basketball, kendo, English, baseball, tennis, brass band, etc.) The student population is very stable with only a few students (three or four) lost each year, generally due to the work transfer of a parent employed by Denka (see community profile). This is supposedly only a fraction of the movement that occurred ten years ago at the height of the 'bubble economy', but firm figures are not available.

The school is of modern design, being built in 1987. It has a large gymnasium, separate assembly hall, twelve classrooms, a multi-purpose room on each of it's three floors, language and computer laboratories, library, a fully independent (but vastly under-utilised) seminar house, two tennis courts, a sports field, sizeable craft/art/ home economics areas, a large staffroom, nursing and recuperation rooms, a board room, and four separate meeting rooms. Located next to the school is 'Sundream Omi' - the local swimming centre used by both the community and local schools.

The teaching staff is well experienced with an average age in the mid-thirties. Most come from the Omi or Itoigawa areas, or now regard the area as their home. Gender balance is roughly 50/50. Due to the ten year limit at one school imposed by Monbusho (Japanese Ministry of Education) an average of two or three teachers per year are transferred or retire. There are two kinds of teaching qualifications in Japan. A two year tertiary teaching certificate, and a four year teaching degree. At Omi chugakko there is a mixture of these qualifications amongst the teachers, but a ratio was difficult to determine. Each teacher is required to attend two compulsory training seminars each year.

As a form of team learning, kaizen (the Japanese ethos of personal and collective improvement) is well practiced and time is set aside regularly for teacher learning and meetings. The staffroom could well be considered, "...a community in which they would not exploit each other, but rather help each other..." (Senge 1990)

Along with a non-teaching principal there are several ancillary staff employed; an administrator, assistant administrator, receptionist, school nurse, and staff clerk. Two janitor/handymen are employed as well, one of whom also assists at the elementary schools and kindergartens. A considered opinion could be that many of the ancillary staff are under utilised, and resources should perhaps be better directed (viz, a student counsellor).

To my knowledge most, if not all, teaching staff believe in and practice the important task of well rounded 'whole-person' education. (Cummings 1980) This 'whole-person' education is reflected in the school philosophy, which is to encourage and build the good character of each student. Omi chugakko strives to instil in its students, 1) a desire for self study, and to further themselves, viz, 'a thirst for knowledge', 2) a strong will, and 3) a kindness toward other people. These goals are not very different from most chugakko in Japan, with the emphasis supposedly on character building, rather than academic results and reflect forms of Japanese Buddhist spirituality. Over recent years the Board of Education has become more focused on academic results, thereby causing a fissure between ideals/goals and reality.

In summary it could be said that the school is well funded and well run, with excellent teaching staff. This is not to say there are no problems, or that none are looming. However, there is nothing at this time creating an awareness or a demand for the community to be more involved.

Profile of present school / community participation and involvement

Parents of students at Omi chugakko are required to involve themselves in the P.T.A. As of last report at least 322 households (out of a possible 344) were involved in P.T.A. activities. Due to the normal working habits of Japanese males the overwhelming majority of parents involved are mothers. It should be noted here that in Japan the mother's role is expressive (influencing educational aspirations) whilst the father's role is instrumental (influencing social and economic status). (Fujita 1978) The P.T.A. is broken down into small groups by activity and town district. These groups meet three to four times a year, and can be involved in activities such as compiling newsletters, and discussing areas of student training. These groups report either to the school principal or vice-principal, who in turn report to the Board of Education.

P.T.A. parents do not work closely with junior high school students/ activities. In elementary schools they involve themselves with events such as sports days, and duties like traffic watch. Perhaps an explanation for a lack of similar involvement at chugakko level could be that it is not encouraged, nor is it usual. With the Japanese emphasis on harmony few parents seem willing to voice any concerns about this. Once a year there is an annual meeting where the school budget is presented, and other various plans for the school year. These are presented as already approved by the Board of Education, and no vote or discussion takes place.

Despite the outstanding facilities of the chugakko, they are not utilised at all by the community. This is probably due to three reasons:

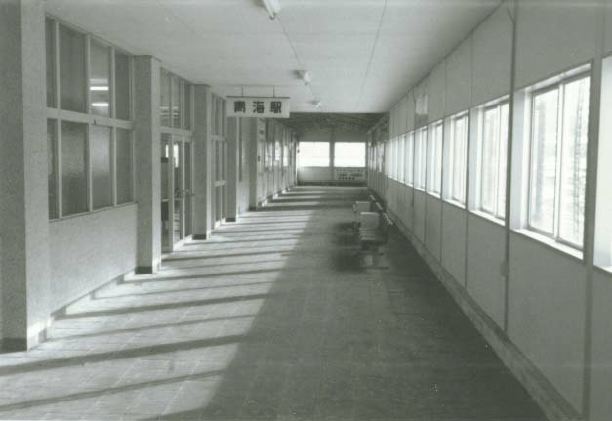

1) The new school was built ten years ago and is about two kilometres from central Omi. The old school was centrally located near the railway station. The former school building was adapted for municipal offices. Some of the other old facilities still remain also (such as the gym, meeting rooms, and baseball field), and have been opened up to community.

2) In Omi there is a lack of organisations such as sporting clubs, interest groups, and adult education classes, that would use such facilities after hours. Those few that do exist use the more convenient old school facilities.

3) The school is perceived by the population as being for the use of students and staff, not as a general community facility.

There are three major annual events where the school and community seem to merge. One is a charity day where students go out into the community to raise funds for charity (similar to a 'Badge Day' in Australia). The other two events are sports day and graduation. Both events draw large numbers of parents (though once again overwhelmingly in favour of mothers), along with local community officials and representatives. Sports day is held on a Sunday to encourage community attendance, and people attending are asked to be involved in certain events.

The conclusion would be that the community on the whole is 'involved' with the school. They take part in various activities that are required of them, but do not appear to have a voice in the running or direction of the school. Ultimate authority lies with the Board of Education. There appears little scope at present for real 'participation' by parents or community in decision making.

A summary of the situation

Like Wrights' (1982) case study school in Gympie, Omi chugakko has,

"...been revealed as a fairly stable institution where the match between parents' values and teachers' values is fairly close in most cases. the similarity in economic and social background of the two is high, and the commitment of both...is similarly strong"

Like times past in Australia, Japan has maintained a huge rate of expenditure per student, seeing it as a quality benchmark. This has certainly been the case in Omi but will change as economic rationalism and the need for lower expenditure per student begin to take hold. Quality will have to be measured in different ways.

However, the community and school has not recognised to any great degree these and other changes occurring in the wider world. To ensure a stable future it needs to address these, along with an attempt by the school to move from being a 'locked door' to a 'balanced door' school. (Copell and Henry 1977) One where the community is participating, the quality of student education is enhanced, and the teaching staff feel comfortable with the increased participation of the community.

There are many benefits that would accrue to the school through this greater participation. However the first problem that must be addressed is how to get the community to realise the needs of the school, to involve themselves in problem solving, and then to 'own' their decisions as a community. As it stands, parents in Omi don't wish to take a leadership role in the school. Working within the 'Japanese way' I believe that this can be overcome, and can only enhance the idea of community.

How will this change come about? No minority pressure groups are established to 'take charge'. There also appears an overriding concern from both within and without that "greater influence by parents and members of the community...[will] lead to a deterioration in the standard of education". (Copell and Henry 1977) Perhaps complacency also plays a role. Radical change is not possible, nor would it be accepted. A successful and efficient school committee must be able to convince both parties that it is actually strengthening both the traditional bonds of Japanese society and the local community by participation, rather than unravelling them.

In the west many teachers and administrators may claim that their hands are bound because the system, "...so protects the individual student that it sacrifices the good of the student body". (Doyle and Cooper 1996) The opposite is probably true at Omi chugakko and, I suspect, the vast majority of schools in Japan. Another challenge is how to get staff, students and parents to act collectively in encouraging personal responsibility and academic excellence. Effective parent - teacher relationships can only help student motivation. (Spring 1983-4)

So ultimately we address the problem. How can the community, school, and board of education move collectively from the present process of community 'involvement', to one of true 'participation' in the day to day activities and running of the school? Specifically there is a need to relieve the pressure on the teachers that comes from involvement in non-academic matters, such as school clubs. There would also accrue many other benefits to the school and community. These will be discussed next.

A specific need and proposed method for change

A lot of "western" teachers lament the time chewed up on peripheral duties outside of the classroom. In most Japanese pre-tertiary schools the teachers are required to be involved with a good deal of non-academic activities, such as after school clubs. These are seen as service for the community good, rather than peripheral activities, and often take in both holidays and weekends. At Omi chugakko it is no different.

However, Monbusho (1981) allows schools flexibility in activities and hours by stating that schools may much make such determination "...in the light of the distinctive characteristics of each school and each community." If the Omi community could involve themselves with these and therefore lessen the teachers non-academic workload there could be several benefits. I will first briefly address the benefits of greater participation, then propose how this need can be attacked. Lastly I will discuss the problems or dangers that may be encountered before a short conclusion.

Benefits

As put by Murnane and Levy (1996), "...the greater part of any solution involves the dull and gritty work of improving the quality of instruction...on a daily basis". If the school was able to lighten the teachers workload there would be more benefit to the students academically. Teachers could focus more on the individual academic needs and well being of each student.

Japan is on the cusp of a new age. It's government is running a huge financial deficit that will soon have to be addressed. Cuts to the education sector will certainly come. By pre-empting the inevitable, and introducing voluntarism the school and community will be better prepared for the new situations that will be encountered. Fortunately voluntarism is a concept being quickly embraced by the Japanese, though maybe not normally at a local level such as this. Awareness and responsibility would also be increased as the community shared with the school a new role as co-educators.

The community would be strengthened, not diminished, by greater participation. The breakdown in community seen in the west could be 'headed off at the pass'. And just perhaps with greater awareness students could be encouraged to stay in the community or return on the completion of higher studies. Oba-san and Oji-san (older people) are revered in Japan, and also possess, "...knowledge, skills and wisdom of a lifetime". (Vacchini 1977) Not only older people but many in the community have a rich resource in skills, and in some cases, time. These could be utilised giving a sense of pride and belonging to the both student and helper. (Wright 1982)

Recommended steps

Initially the school and board of education would need to be convinced of the need, and support it. This would take quite some arguing, planning and time. However for the purposes of brevity in addressing the problem we shall assume approval and support is being given to the administrator by the school and Board of Education

Step one is the need to raise awareness within the community. Because there is less disparity in Japanese society one does not need to deal with a segmented community. However, the Japanese are loath to speak out, so therefore I think an excellent first step would be the distribution of a questionnaire, both about needs and proposals for greater participation. The advantages of this would be,

"...anonymity which encourages parents to feel they can say what they feel without fear of repercussion, it can be completed anytime, it can be brief, and the respondent has the chance to think carefully before answering". (Beacham, et al, 1981)

In Omi home visits by teachers are quite common, and these could also be used to facilitate private discussion in a congenial setting. Parents must feel comfortable in discussion with school staff, whether it be at home, at school, or some mutual meeting place. Whichever procedure is used the school must ensure that a mechanism is in place, "...whereby the needs of the community can be monitored". (Vacchini 1977)

The Japanese have a great pride in being able to settle problems in a convivial atmosphere. This usually involves getting together at an enkai (drinking party) and imbibing copious amounts of alcohol! As unusual as we may find this concept in the west it is very much part of 'the Japanese way'. It at these times that people are expected to say what they truly think. Therefore, organising enkai may prove useful as a tool to encourage the more reticent and wary amongst the community. It may even get more males to come and be involved!

Next the school should encourage the community to come in and use their facilities. Also, at present the school has no 'open days'. These should be undertaken regularly in an effort to make the community proud of 'their school'. Denka Ltd. could be approached to sponsor these and maybe some of the awards that are regularly presented at the school. The community feels a large obligation to Denka and this would set a good example. From this point it will be easier to have the community participate in activities like after school clubs.

Initially there would have to be a 'club volunteer coordinator(s)' co-opted from staff along with representatives of the volunteers. After an orientation period (presuming that the handover of responsibilities proceeds smoothly) the volunteer representative or committee could then report directly to the Principal or Board of Education. Teachers could still play minor roles in oversight, but would now be free to concentrate more on helping to achieve academic excellence in their students.

Problems and dangers

No solution is without it's problems and dangers. In Omi the problem is one of deep rooted conservatism and the danger of moving too quickly. A well known magazine concluded that, "Japan changes so it can stay the same." (Fortune Magazine 1996) Astute school members must read the signs carefully and move at an adequate pace, all the while gaining consensus along the way.

In addition to this community influence must be taken into account. This is because,

"...the school, however separated it may appear as an institution, is still an integral part of the community and responsive one way or the another to various kinds of community influence, direct or indirect". (Blakers 1983)

There is an obvious danger in ignoring this surreptitious influence, particularly in a community like Omi.

Conclusion

In conclusion I can see many benefits emanating from the greater participation of the community at Omi chugakko. The community being involved in after school clubs is just one small step in a larger process. In a final sense schools are for the benefit of students, but this in turn ultimately benefits and builds community. Japanese schools like Omi chugakko must absorb new ways of thinking whilst still drawing on the old, which in the tradition of nihonjinron is clearly possible.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ABC Television News (1999, July 29)

Bambach, J.D. (1977). The Community and Education, Australian College of Education, Carlton, Victoria.

Beacham, et al. (1981). Techniques for Participation in Decision Making for Previously Uninvolved Groups, A School and Community Project, C.C.A.E., Canberra

Blakers, C. (1983). 'Having a say: Parent participation in decision-making', in Sociology of Education, Browne, R.K. & Foster, L.E., (Ed.), Macmillan, Melbourne

Coppell, W.G. & Henry, B.E. (1977). The Community and Education, Australian College of Education, Carlton, Victoria,

Cummings, W.J. (1980), Education and Equality in Japan, Princeton University Press, N.J.

Daily Yomiuri (1996, August 30)

Doyle, D.P. and Cooper, B.S. (1996, September 9). 'Religious Schools Can Be a Solution ' Washington Post - Outlook,

Fortune - International Edition (1996, August 26).

Fujita, H. (1978), Education and Status Attainment in Modern Japan, PhD thesis, Stanford University

Honen (1988). Nippon, The Land and its People, Gakuseisha Publishing Co. Ltd, Tokyo.

Iwashita, T. (1992) 'Why I quit the company' in New Internationalist, Vol. 231

Maroya, L.C. (1985). 'The small school as the symbiosis of a caring community', Unicorn, Vol. 11, No. 3.

Nisbet, R.A. (1962). Community and Power, Oxford University Press, New York.

Monbusho: Japanese Ministry of Science, Education, and Culture, (1981), Outline of Education in Japan

Murnane, R. and Levy, F. (1996, September 30). 'The ABC's of Reform', Washington Post - Outlook,

Senge, P.M. (1990), The Fifth Discipline, The Art and Practice of the Learning Organisation, Doubleday Currency, New York

Singleton, J., (1967) 'Nichu: A Japanese School', Case Studies in Education and Culture, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York

Spring, J. (1983-4) 'Involving the total school community', A Case Study of Inala School, Brisbane

Vacchini, I. (1977) Demystifying Community Research Techniques, Collins, J.E., Telfer, R.A., & Everett, A.V., (Ed.) University of Newcastle, N.S.W.

Wright, C. (1982). A Study of Parent/Community Participation in Australian Schools. Independent Study Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Bachelor of Education.

© 1993-2008, Nicholas Klar, PO Box 280, Brighton SA 5048, AUSTRALIA

May be reproduced for personal use only. Any reproduction in print or in any fixed or for-profit medium is not allowed without written permission. If any of these pages are copied, downloaded or printed the copyright statement must remain attached.

Any use of this or other works for academic and/or other research must be duly acknowledged by bibliography or reference.

REF: Nicholas Klar, 1993, "Social Change in Rural Japan and the Need for Community Involvement - A Case Study" - www.klarbooks.com/academic/change.html + date accessed

| The Klar Books Site | A "life in Japan" on the "JET Program" book | |

|

|

||

Essay: "Social Change in Rural Japan and the Need for Community Involvement - A Case Study"